Submitted by Rachel Fellows on Tue, 15/04/2025 - 18:03

Researchers at the MRC Toxicology Unit have identified that the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole shows similar gastrointestinal side effects in fruit flies as in humans. For the first time they linked the mitochondria damaging effects of aripiprazole to death of the cells lining the intestine. Feeding the flies with an antioxidant supplement along with aripiprazole substantially reduced the damage to the intestine.

When drugs are taken by mouth they are absorbed by cells lining the intestine so that they can enter the bloodstream and reach their target. As all drugs have side effects, that means that intestinal cells can be affected even if the drug isn’t treating an intestinal disease. Some of the most common side effects of drugs such as constipation, indigestion and diarrhoea relate to their effects on the gastrointestinal system. However, we still don’t know much about why these happen because it is difficult to study intestinal cells directly in humans.

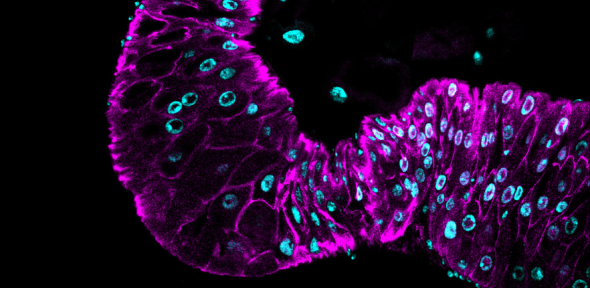

Enter the fruit fly, known to scientists by its Latin name Drosophila melanogaster. At only 3-4 mm long, these flies are cheap to look after and have a similar gut structure to humans, making them the ideal subjects to study why different drugs cause unwanted effects on the intestine. “Use of a simple model system like the fruit fly allows us to investigate these side-effects while reducing our reliance on mammals in toxicology research” says James Hurcomb, co-first author on this study.

Aripiprazole is a commonly prescribed antipsychotic medication, used to treat conditions including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Although aripiprazole has less side effects than previous generations of this type of drug, intestinal side effects are still common. “Every cell needs to produce energy, and this function is carried out by a special tubular network of subcellular structures called mitochondria” explains Amrita Mukherjee, also co-first author of this study. “We found that aripiprazole damages the mitochondria of gut epithelial cells, resulting in their death, in a fruit fly model.”

This death of intestinal cells was due to the production of reactive chemicals called reactive oxygen species and this effect was reduced by giving the flies antioxidants to mop up these toxic reactive species. Importantly this intestinal toxicity involved a pathway that is also present in humans. “This is as fruit flies share many genes with humans. The pathways that respond to aripiprazole toxicity are also present in humans, meaning there is a promising avenue for future research in this area, and potential impact on patients” says James.

Amrita adds “Although this requires further investigation, our study implies that there is a possibility of mitigating the gastrointestinal side effects of orally administered antipsychotic medication for patients in a non-invasive manner.” It is worth noting that there are many antioxidants that work in different ways, and can potentially increase side-effects of medications, so should only be taken if prescribed.

These findings have wider implications for how we treat patients with drugs that have unintended effects on the mitochondria and provide a method for how to study side effects in a complex system such as the body. James explains “Our study shows the value of using alternative model systems to understand the physiological side-effects of drugs, which are impossible to model using cell culture alone meaning that an animal model is required”.