Submitted by Anonymous on Tue, 03/11/2020 - 10:20

Immunotherapy can be a lifesaver for cancer patients, but some patients' tumours don't respond well to this treatment. However, researchers are encouraged by a recent clinical trial that suggests that it may be possible to expand immunotherapy to help more people in the future.

Immunotherapy works by marshalling the body's defences against cancer. In particular, drugs known as “immune checkpoint inhibitors” can stimulate the immune system to attack cancer cells. However, immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been effective against tumours with low levels of genetic mutation. Some of these tumours seem to be able to engage an additional immune suppressive pathway that repels the immune cells.

In a recent research project, a team from the U.K. and a team from the U.S. collaborated to test a drug called plerixafor that they hoped would interrupt this immunosuppressive pathway and let the body's natural defence system work.

The clinical trial involved 24 people with either pancreatic cancer or colorectal cancer. The patients all had advanced disease of a type not expected to respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors. They received plerixafor intravenously for a week. Researchers biopsied metastatic tumours from each patient before and after treatment. Lab analysis of the samples showed that immune cells had invaded the tumours during the treatment with plerixafor, suggesting that it may allow immune checkpoint inhibitors to do their work.

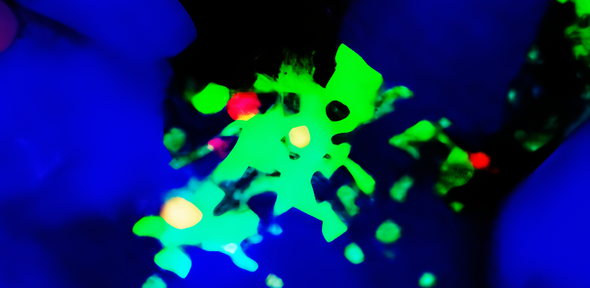

Daniele Biasci (CAMS Research Fellow, MRC Toxicology Unit, University of Cambridge), who led the computational immunology analyses of the study said: “These results are very encouraging. The gene expression patterns induced by plerixafor in this study resemble the ones observed in tumours who respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors”. Among the immune cells that had attacked the tumours, researchers found fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs), a special type of cell that organizes other immune cells to mount a response.

The study brought together scientists from the University of Cambridge (UK), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (US). The team was led by Duncan Jodrell at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute and by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory scientists Douglas Fearon and Tobias Janowitz. The study included clinical collaborators at Weill Cornell Medicine, NY. Daniele Biasci is first author of the study, supported by a Cambridge Alliance on Medicines Safety Research Fellowship (University of Cambridge, AstraZeneca and GSK) and he is based at the MRC Toxicology Unit, University of Cambridge. The study paved the way for a Phase 2 clinical trial, which will combine plerixafor with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Citation

Biasci, D., et al., “CXCR4 inhibition in human pancreatic and colorectal cancers induces an integrated immune response”, PNAS, October 30, 2020. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2013644117

Funding

Cancer Research UK, the Lustgarten Foundation, Stand Up To Cancer, CK Hutchison Holdings Limited, the University of Cambridge, The Atlantic Philanthropies, National Institutes of Health, Pershing Square Foundation, and NIHR/CRUK Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, Cambridge Alliance on Medicines Safety.

Figure description

Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) coordinate immune responses to cancer cells. In this image, a single fibroblastic reticular cell is identified, by staining it: the cell nucleus (blue), markers that identify fibroblast cells (red), and a molecule that attracts immune cells (green).