Submitted by Rachel Fellows on Mon, 30/06/2025 - 16:50

Researchers in the Patil Lab have discovered that certain species of bacteria found in the human gut can take in and store PFAS, also known as ‘forever chemicals’. Boosting these species in our gut microbiome could be a new way to protect us from the harmful effects of PFAS.

Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are used in wide range of products such as non-stick pans, carpets and fire-fighting foams because of their useful heat resistant and water and grease repelling properties. However, these man-made chemicals are so notoriously difficult to destroy, that they have been nicknamed ‘forever chemicals’ and are widespread in our environment.

PFAS were originally thought to be safe because they don't react with biological molecules, but it’s now clear that they’re not. Longer more ‘sticky’ PFAS can hang around for years inside the body, building up the in liver, kidneys and other organs. According to recent studies, most individuals have detectable levels of PFAS in their blood. PFAS are linked to an increased risk of several diseases including reduced immunity and developmental defects in children, increased cholesterol levels and cancer.

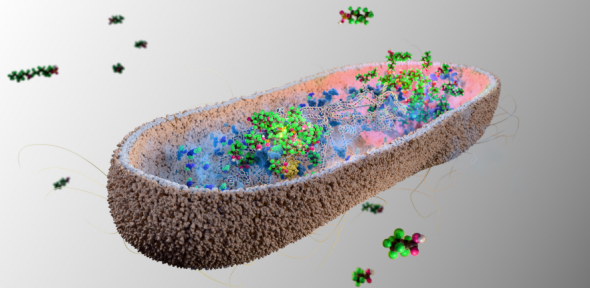

Scientists at the MRC Toxicology Unit found that certain bacteria, including Bacteroides and Odoribacter species that are commonly found in the healthy human gut, can absorb various PFAS molecules from their surroundings. When a cocktail of these bacterial species was introduced into the guts of mice to mimic the human microbiome, the bacteria rapidly accumulated the PFAS present in the mice. The bacteria with PFAS inside were then passed out of the mice in the faeces.

The researchers also found the bacteria could still accumulate the same percentage even when they were exposed to very small or very large amounts of PFAS. Within minutes of exposure, the bacterial soaked up between 25% and 74% of the PFAS, depending on which species was tested.

Dr Kiran Patil, senior author of the study said, “We found that certain species of human gut bacteria have a remarkably high capacity to soak up PFAS from their environment at a range of concentrations, and store them in clumps inside their cells. Due to aggregation of PFAS in these clumps, the bacteria themselves seem protected from the toxic effects.”

Current treatments to remove PFAS are limited and have significant side effects. They involve either replacing the patient’s blood with donated blood or the use of Anion Exchange Inhibitors (AER), drugs that bind bile acids and have been approved to treat high cholesterol. This finding that certain species of bacteria present in our gut can take up and store PFAS, provides new hope for an effective treatment to remove PFAS from our bodies with minimal side-effects - although this has not yet been directly tested in humans.

Dr Indra Roux, a researcher at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit and a co-author of the study said: “The reality is that PFAS are already in the environment and in our bodies, and we need to try and mitigate their impact on our health now. We haven’t found a way to destroy PFAS, but our findings open the possibility of developing ways to get them out of our bodies where they do the most harm.”

With serial entrepreneur Peter Holme Jensen, Lindell and Patil have co-founded Cambiotics, a start-up that is developing probiotics that remove PFAS from the body. Anna explains, “We are working to take the finding from the lab that gut bacteria can accumulate PFAS and turn into a product that can help detoxify the body from PFAS. We're taking highly accumulating bacteria and we're putting them into a capsule format that you can take.” Cambiotics is supported by Cambridge Enterprise, the innovation arm of the University of Cambridge, which helps researchers translate their work into globally-leading economic and social impact.

While we wait for new probiotics to become available, we can prevent some PFAS from entering our bodies. The researchers suggest avoiding PFAS-coated cooking pans and using a good water filter.

The research was funded primarily by the Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health and Care Research, and Wellcome Trust.

The study, ‘Human gut bacteria bioaccumulate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances’, was published in Nature Microbiology on the 1st July 2025. Read the full article here Human gut bacteria bioaccumulate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances